...(and what we can do about them). Although these posts are primarily sketches for a book project on environmental critique I will also post from several other ongoing projects.

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Saturday, November 26, 2011

Friday, November 25, 2011

Sunday, November 20, 2011

Wednesday, November 16, 2011

Soil Microarthropod Contributions to Decomposition Dynamics turns 100

According to a recent Google scholar alert (emails I receive when others have found use in their work for my publications), a paper I wrote with a number of colleagues connected with the Institute of Ecology at University of Georgia over a decade ago has now been cited in other works more than a hundred time. This is not a huge number of course (citation classics in ecology are cited thousands of time) but nonetheless it is gratifying. A lot of work went into the paper, and it involved fun but sweaty times in Costa Rica, Puerto Rico, and the Southern Appalachians where I examined decomposition rates of leaf litter (there was one common substrate - Quercus prinus - across all sites). I can measure out the cost of this paper in bot-flies in my flesh, but that's another story!

As far as I can tell when people want support from the literature to support the overwhelmingly obvious statement that decomposition rates are higher in the tropics than in the temperate zone they cite Heneghan et al 1999. Another less obvious outcome of the work has rarely been discussed and that is the observation that in warmer and wetter parts of the world the influence of soil critters can becomes quite important in determining decomposition rates. Small differences in the assemblage structure of soil biota at different sites can have an influence on decomposition rates and on the rate at which nutrients become available in the soil. In the graph above the CWT site is a temperate one (Coweeta), that LUQ site is Luquillo Forest in Puerto Rico and the LAS is La Selva in Costa. When soil microarthropods (mites, springtails, coneheads etc) were excluded there is a difference between the temperate and tropical sites in the rate of litter breakdown, but no difference between the two tropical sites (upper panel). In the lower panel the soil critters had access to the litter and a fairly pronounced difference emerged between the two tropical sites (expressing the influence of unique soil faunal assemblages on each site).

As far as I can tell when people want support from the literature to support the overwhelmingly obvious statement that decomposition rates are higher in the tropics than in the temperate zone they cite Heneghan et al 1999. Another less obvious outcome of the work has rarely been discussed and that is the observation that in warmer and wetter parts of the world the influence of soil critters can becomes quite important in determining decomposition rates. Small differences in the assemblage structure of soil biota at different sites can have an influence on decomposition rates and on the rate at which nutrients become available in the soil. In the graph above the CWT site is a temperate one (Coweeta), that LUQ site is Luquillo Forest in Puerto Rico and the LAS is La Selva in Costa. When soil microarthropods (mites, springtails, coneheads etc) were excluded there is a difference between the temperate and tropical sites in the rate of litter breakdown, but no difference between the two tropical sites (upper panel). In the lower panel the soil critters had access to the litter and a fairly pronounced difference emerged between the two tropical sites (expressing the influence of unique soil faunal assemblages on each site).

Sunday, November 13, 2011

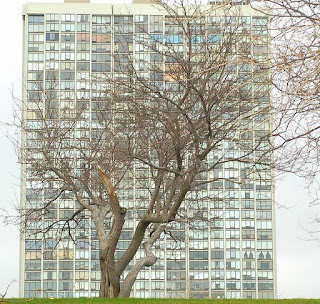

Metempsychosis

“They believed you could be changed

into a tree from grief”

(Ulysses, James Joyce)

And now you are the tree – the corruptible

Transformed into the certainty of wood,

Your roots, more expansive than your crown

Ploughing the hectic-stable earth,

Your leaves – sun-soaking and ground-shading –

Reflecting the jig of time

In the simplicity of the fall,

And in the lentic stillness of livid branches –

Offered up to appease a lurid sky

You buffer the grief of the world.

Friday, November 11, 2011

Deep, Dark and Shameful: Morton and Jordan and Our Ecological Futures

Over the coming weeks I will be re-reading books by two authors who have been important to me in recent years: William Jordan III's The Sunflower Forest: Ecological Restoration and the NewCommunion with Nature and his new Making Nature Whole: A History of Ecological Restoration, as well as Tim Morton's Ecology without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics and The Ecological Thought.

Over the coming weeks I will be re-reading books by two authors who have been important to me in recent years: William Jordan III's The Sunflower Forest: Ecological Restoration and the NewCommunion with Nature and his new Making Nature Whole: A History of Ecological Restoration, as well as Tim Morton's Ecology without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics and The Ecological Thought.

In particular I am interested in the relationship between two terms in these books: "shame" in Bill Jordan's work and "dark" in Tim Morton's work.

Briefly, Bill regards the jettisoning of shame in contemporary culture (or the desire to avoid shame) as being problematic since it is through our grappling with shame that, arguably, we get to transcendent values such as beauty, meaning and community (in this he is drawing upon the work of critic Fred Turner). Shame is differentiated in this account from guilt in as much as the former is not necessarily associated with wrongdoing. Rather, shame is the painful awareness of limitation or shortcoming - existential shame as Bill qualifies it. For instance, I personally feel the hot sting of shame twice each week in my French translation class, not because I have naughtily neglected my homework (when I do, I may feel guilty) but because my woeful facility with this language becomes publicly apparent. Especially significant for Bill is that ecological restoration, unlike many other forms of ecological activity (or inactivity - i.e. environmental asceticism: see here or a shorter version here) provides an encounter with shame, or to put it as Bill does, it "implicates the restorationist in the universal scandal of creation [and] provides a context for achieving communion with creation." To deal with shame then is to willfully tussle with the less seemly aspects of existence, rather than to ascetically disengage from the world with all it problematic aspects.

A Brutal Dance - Topic of my 3Quarks Column Monday

If I can get it finished to my satisfaction I will post a piece on Monday from my memoir written using the framework of momentous or embarrassing dancing incidents, of which I have had very many. A snippet here: I will link it up to 3qd on Monday morning

From my autobiography

in progress “My Life in Dance – a Motional History of my Body”

I wish to set out here my own experiences with dance as

honestly as good taste will permit. I

have a body, one that is a little succulent and that moistly disinclines when

bidden to perform arts of great strenuousness.

It is not a body apt to move all that prettily. For all of that, I have tried to bend it to

my will, commanding it often enough to skitter across the floor in a rhythmic

and frolicsome fashion and I have witnessed its failure with displeasure. Though I can leap and skip and jump and hop, the

sum of these gyrations don’t seem to add up to dance.

However, in perverse inverse to my skill, dancing has been a component

of several of my more arresting developmental moments. I relate one here.

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

Robinson Jeffers' Inhumanism: The Ecological Thought or The Misanthropic Rebuke?

I have been rereading poems by Pittsburgh born Robinson

Jeffers (1887 – 1962) with my seminar class recently. Jeffers has had a perennial appeal for

environmentally-inclined readers, with his wilderness inflected meditations on

his adopted home on the California coast.

The poems that I know (I am a Jeffers amateur) are sturdy rather than pretty, and charged with

solid thought rather than airy abstractions.

Though there has been some discussion among the critics about his influences

(was Schopenhauer as important to him as Nietzsche?) what strikes me are the thematic

resonances with on the one hand American environmental writers both

before and after him and, on the other, with themes from the Upanishads (which I

am reading with another class).

The influence of the Upanishads, philosophical texts in the

Hindu tradition, on Emerson and Thoreau is pretty well known. The Upanishads were also famously a source

for Schopenhauer (and Schopenhauer, of course, exerted a substantial influence on

Nietzsche). Finally, these texts also influenced W B Yeats, whom Jeffers

admired (see this post). The Upanishads rest at the intersection

therefore of many of Jeffers’ more important inspirations. From this influence Jeffers can create striking

things. In The Answer (1935), for example, he writes:

“A severed hand/ is an ugly thing, and a man dissevered from the earth and the stars and his history…for contemplation or in fact… /Often appears atrociously ugly. Integrity is wholeness, the greatest beauty is/ Organic wholeness, the wholeness of life and things, the divine beauty of the universe.

Thursday, November 3, 2011

Home is born in motion

(I wrote this a while ago, but was getting nostalgic for it...so reproducing it here)

Leaving home is a violent act, because walking is a violent act. Walking violates a stationary calm and announces, "this place does not satisfy my needs anymore", or, "having served its purpose once, this place now bores me". Walking derives, anciently – phylogenetically – from motile carnivory. It is rooted in impatience – the primordial impatience with waiting for morsels to waft on by. Motility is the ancestral condition. Life was born on the move. Flagellated, ciliated – gliding, and lashing – permanently unsatisfied and desirous. Motility is the characteristic act of animality. In their evolutionary procession, animals squirmed, wriggled, pulsated, swam, slithered, and later, lurched, crawled, leapt, hopped, flapped, flew, swarmed, brachiated, knuckle-shuffled and then most recently arose and walked away. Not the chosen option: repose is abandoned. A singular spot is forsaken. Beasts leave home to prowl and stalk, to kill and dine. Pursuing other options, bathed in the sunlight, were animals enduring cousins in the kingdom of plants. Left behind also: sessile brothers, animals hedging their bets by fiercely equipping with lures and tackle and macerating jaws.

Leaving home is a violent act, because walking is a violent act. Walking violates a stationary calm and announces, "this place does not satisfy my needs anymore", or, "having served its purpose once, this place now bores me". Walking derives, anciently – phylogenetically – from motile carnivory. It is rooted in impatience – the primordial impatience with waiting for morsels to waft on by. Motility is the ancestral condition. Life was born on the move. Flagellated, ciliated – gliding, and lashing – permanently unsatisfied and desirous. Motility is the characteristic act of animality. In their evolutionary procession, animals squirmed, wriggled, pulsated, swam, slithered, and later, lurched, crawled, leapt, hopped, flapped, flew, swarmed, brachiated, knuckle-shuffled and then most recently arose and walked away. Not the chosen option: repose is abandoned. A singular spot is forsaken. Beasts leave home to prowl and stalk, to kill and dine. Pursuing other options, bathed in the sunlight, were animals enduring cousins in the kingdom of plants. Left behind also: sessile brothers, animals hedging their bets by fiercely equipping with lures and tackle and macerating jaws.

Tuesday, November 1, 2011

First regular post on our new DePaul Institute for Nature and Culture blog today

This is how Randall Honold kicks us off in a piece called Living with Objects

My first blog post, my first public confession: For some time now I’ve been living with objects. They kind of snuck up on me, insinuated themselves into my life, and now they won’t go away. Not that I’m complaining. Not that I feel guilty about taking a break from my former relationships. For the longest time, you see, I thought I was in relationships – living with objects, sure, but getting to know them meant understanding all we did for each other. These relationships seduced me into thinking they were pretty much all that, that I’d never get anything more out of the arrangement, that there’s no sense in wanting something more from objects because I can’t have it anyway. Now that I see I’ve been with objects all the while and relationships have been coming between us, I’m starting to see why all the fuss about objects.Read on here

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)